Extracted

from an essay by Leah Lipton, Charles Hopkinson: Pictures from

a New England Past, Framingham Massachusetts, Danforth Museum,

1988.

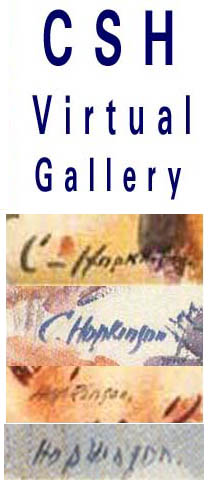

Charles

Hopkinson

1869-1962

Charles

Hopkinson enjoyed an active and successful painting career that

spanned more than sixty years and brought him honors and acclaim.

Today, his reputation rests largely upon the commissioned

portraits of prominent men which are now in public collections:

university presidents and professors, lawyers, bankers, philanthropists,

poets. Often called the "court painter of Harvard" because of the

thirty or more portraits he produced for that institution, he found

original and vivid ways to paint the conventional official portrait.

But Hopkinson was equally well-known in his lifetime for his bold

and innovative watercolors, and

his evocative portraits of children.

Both are virtually unknown to today's public because most of these

paintings are in private and family collections. This CSH Virtual

Gallery provides an opportunity to acquaint ourselves with these

two facets of his talent, and to reassess, in modern terms, an important

Boston artist.

From

as early as 1900, Hopkinson's work was frequently exhibited and

widely reviewed, almost always in superlatives. His 1928 one-man

show at the Montross Gallery in New York was called "the outstanding

watercolor event of the year, and this includes the Marin exhibition.... the most dazzling conjuring of color and form in the new expressionistic

mode that any American artist has accomplished in this medium."

Henry McBride, the noted critic for the New York Sun, wrote in May,

1925, "It appears that he is our best... it would be difficult to

discover in our midst a portraitist of more all round competence."

Again in the Sun, in January, 1931, a second reviewer declared,

"About the strongest card we have to play against the avalance of

French art that confronts us this week is Charles Hopkinson, the

ace of American portrait painters." His popularity did not diminish

throughout his long life. In 1948, Time Magazine called him "the

Dean of U.S. portraitists," and Boston Globe critic Robert Taylor

echoed this phrase in 1953, adding that Hopkinson was, at the age

of eighty-four, "just as revolutionary, in his own way, as the

vanguard of the latest style."

When

he was not working on commissioned portraits, he painted his family

or himself. There are more than sixty self-portraits

still in the studio on the top floor of his Manchester house. He

seems to have used these not only as direct and honest records 'of

his changing appearance, but also as vehicles for problem-solving,

for testing ideas relating to light and shadow, brush techniques

or methods of modelling the human face. The self-portraits in this

exhibition include both the earliest known example, painted before

the turn of the century, and the last, a brutally honest work painted

in 1961, when the artist was in his ninety-first year. Although

not offered for sale, Hopkinson's pictures

of his children were a staple of his exhibitions in the first

decades of the twentieth century. One of the artist's children said

recently, "We all thought it was the duty of every child to sit

quietly while her father painted her." She recalled that her mother

would read aloud to them as they sat, and when they got too "wiggley," they were allowed to get up and move around for a while. The

sittings, she thought, lasted about an hour at a time.

Family

legend gives credit to John Singer Sargent for suggesting the theme

of Three

Dancing Girls to Hopkinson, after seeing the girls dressed in

old-fashioned costumes, dancing on the rocks at Manchester. Sargent

visited the Manchester house in 1916 while he was in Boston working

on the murals at the Public Library. A postcard from one of Mrs.

Hopkinson's sisters to another, written on August 20, 1917, confirms

a second Sargent visit, in the company of Isabella Stewart Gardner.

Harriot Curtis writes, "John Singer [Sargent] admired it ex-tremely!

[a reference to the dress worn by one of the girls] He and Mrs.

Gardner, no less, came by tother (sic) day to see how the painting

he insisted on Charles painting came on. He likes it but says there

must be four, not three, children, and Happy must be definitely

curtseying." Although Hopkinson did not add a fourth child, there

is evidence in a study he made for the painting that he did change

the position of the child in the foreground in response to Sargent's

suggestion.

While

pre-eminently a portrait painter, Charles Hopkinson painted watercolors

all his life, for his own pleasure, as a relief from the pressures

of accomodating (sic) a client, and as an intense personal response to

the landscape and the sea. Although they were widely exhibited and

well received, he was reluctant to sell them, and most of them are

still in the hands of family and friends. Perhaps half of them were

inspired by the dramatic view from his house in Manchester and the

others document an equally strong response to nature in many places

around the world. Among the more than 700 extant watercolors are

scenes from California, Hawaii, Bermuda, Venice, Paris, New Zealand

and Ireland.

Hopkinson's

expressed goal in painting the water-colors was to capture the "heart"

of the scene. Foreground details, he said, had to be seen "out of

the corner of the eye," while the focus in the center must be portrayed

with vigor and accuracy. His is a highly selective style which rejects

the non-essential and casts aside cliches. He painted very quickly,

making rapid decisions. Although some of the early works are factual

and descriptive, most of his watercolors are rapid distillations

of the essence of the scene. In Kite

Flying Day, Ipswich, for example, the gaiety of a crowd of people

is conveyed by a few swiftly applied flecks of color.

He

tried, he said, to see with the "innocent eye, not the intellectual

eye," that is, to allow the impact of the scene before him to determine

his approach. In 1928, he instructed his daughter Ibby that one

must have "nothing but humbleness before nature, an intelligent

humbleness, an emotional response...."

|