AN ARTIST AT WORK

BY

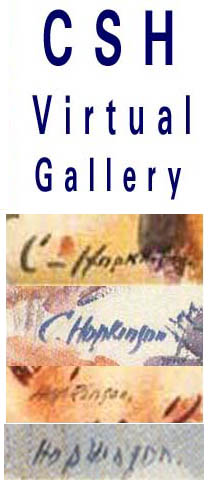

Charles Hopkinson

For the Examiners Club

October 1947

[Submitted

by the artist's daughter, Isabella Halsted]

When

I found I was to give a talk here, I asked one of our members what

I should talk about. Said he: "Tell us what a portrait painter

thinks about and does when he is at work. We don't know at all".

So here goes, and if I use the word "I" too often, it

is because I remember what Professor Lebaron Briggs wrote on the

margin of my daily theme: "Nobody is interested in what 'one'

does or thinks, tell us what you do and think".

I wish

I could convey to you the excitements, the temptations, the satisfactions

of an artist's life. It is full of adventure, disappointments and

assuagements. The artist at his worst is an exhibitionist, at his

best a seeker after truth, and never satisfied with what he has

found or accomplished. What are his motives, what makes him become

an artist? A desire to set down in his own sight, so that he can

enjoy them again, the sensations he had when he was impressed with

what he calls beauty. The wish to have his work admired leads to

exhibitionism and to conceit in his achievement. To balance this

is a true reverence for the beauty he sees, a humbleness before

Nature, a wish to be the servant of beauty.

What

makes an artist? The normal human being looks at things for utilitarian

purposes; he has elements of the artist in him if he takes pleasure

or pain from the appearance of things and only secondarily notices

what may be called their utilitarian qualities. The normal human

being enjoys repetition. He is comfortable with the familiar. The

artist enjoys the repetition of line or form in a design-perhaps

for the same reason? The primitive man, when he was an artist, as

you remember, made designs on his pots full of repetition.

How

much does the layman, as I will call him, appreciate why he enjoys

what he calls the beauty of a tree, or even a pretty face? It all

lies really in the matter of design. The tree has symmetry, either

obvious or irregular; again, all its leaves are the same shape,

but with enough difference to destroy monotony. If the pretty girl,

the curve of whose nose is the reverse of her chin and her jawbone,

but is the repetition of the curve of her eyebrow, has curls in

her hair which repeat the curve of her nose, so much the more is

the pleasure of the sight of her.

The

Western World thinks of pictures as representations, as subject

matter, which, if it is familiar, gives pleasure; if not, does not

please so much. But no picture is really good which has not the

element of design.

When

I had finished a portrait not long ago the artist who had lent me

the studio looked at it a good while, then made comments on it as

a picture, and finally said: "And it is a good likeness, too,"

evidently not the most important part of it. But who, of the lay

world, who knows the sitter, does not first speak of the likeness?

Of course we all know Sargent's description of a portrait: A likeness

in which there is something wrong with the mouth. I think a portrait

must be a likeness; I take that for granted. But no portrait will

live which does not have a fine pictorial design, regardless of

subject.

A portrait

painter, as much as a landscape painter, should be a maker of pictures.

No portrait that is not interesting aesthetically has stood the

test of time. It should please, interest and move the observer by

its design, as a piece of music does. It should have a pattern of

shapes and areas and lines, of gestures and masses and contrasts

of light and dark, of harmonies and contrasts of color. It should

have, not a facsimile of the person represented, but a description

of him or her made with intense emotion. The matter of design, I

rather think, is chiefly an intellectual proceeding, but when it

comes to the delineation of the sitter, then the artist must become

almost an emotional actor. It is not that he tries to imagine what

sort of a person his sitter is, but he must feel in his whole nervous

system the gesture of the sitter's body, the grasp of a hand, the

curve of a mouth.

The

painter for his own satisfaction is an observer. He must make himself

so sensitive to his visual impressions that his feelings of pleasure

and pain are affected. This habit has a marked effect on the artist's

character. He may become so much in the habit of letting himself

be moved by what he sees that he becomes cowardly and shrinks from

unpleasant experiences. He is a poor kind of help in a sickroom.

On the other hand he is made happy and moved to an ecstasy of feeling

akin to a religious experience by something in the visible world

that the layman perhaps never even sees.

I am

not scornful of the layman; I am one half the time. I can go my

way like a layman and can understand why he acts as he does. I can

look at the harmonies of color on my plate and not see them; they

are only things to eat. I have arranged flowers at home as if I

were painting a picture, and then can go out to dinner and never

see the centerpiece my hostess has arranged with such taste and

care because I am interested in what my neighbor is saying and what

she may think of me. I am reacting to life as a human being is intended

by nature to react, not as an artist who by some natural idiosyncrasy

and by cultivation has learned to act as he does.

An

artist must see everything as a picture. His picture must be made

by choosing among the innumerable characteristics of what he is

looking at those he is going to use to make his picture. He may

emphasize the color and hardly make any form at all. He may make

the form in monochrome. We are all familiar with the convention

of the black and white. Why not accept any other convention? A red

chalk drawing of a landscape with trees is accepted, why not a head

done in green chalk? When an artist makes a landscape where objects

are only suggested with swift strokes he may be painting with all

his might, all his soul wrapped up in trying to state the particular

beauty he sees which can be suggested in no other way. It is called

a hasty sketch but it is really a greater work of art because it

has more spirit than the care-taking finished large painting he

may make from it.

He

has made his picture and the ideal layman who looks at it should

be moved as the artist was moved. He should take it for granted

that the artist knows his job as well as the doctor knows his, but

how is the layman, preoccupied with business and life, to do this?

I don't know, but at least he should humbly try. Probably one of

the best ways to learn is to become an amateur artist, and to become

accustomed to describing sensations vis-a-vis to nature by symbols;

for after all the shapes an artist puts on canvas or paper are symbols

to describe what he feels. In what is called modern art a new set

of symbols is used. I think we should take for granted they are

sincere expressions and learn them in order to enjoy the pictures.

What

I understand to be the Academic procedure is the copying of the

aspect of the subject, all the accidents of light and shade, everything,

just as an unthinking camera would do. To imitate nature, however,

is to make use of the principles by which objects seem to be made

and recreate an image according to the laws of nature. Imagine a

white candle with the lights shining on it from two sides and in

front, so that there is no shadow or shading on it. If you copy

it faithfully as it looks, you will succeed in making a flat oblong

white shape. If you imitate nature using what your two eyes tell

you about that candle, you will make it look round by artful means,

by putting lighter and darker areas upon your oblong shape. A portrait

should be a re-presentation of the sitter. The person in the picture

should exist in the world of Art, not in our world in a mirror.

The illusion of space in the background should be designed in depth

as much as it is designed vertically and horizontally. The illusion

of solidity of the figure should be obtained by artful means based

on the phenomena of light and shade and color on form. In that way

the artist can make the illusions of existence in space, whereas

if he copied what was before him he would find certain forms camouflaged

by accidental reflections, so that they are flattened out, as in

the example of the candle.

I will

diverge here by asking if this making the illusion of form in space,

which is expected as a matter of course in most of Western art,

is perhaps only a parlor magician's trick? When a Japanese or Chinese

was first shown such a picture, he touched it with his finger, saying,

"You can't fool me. That is only a flat canvas." I am

fascinated by this illusion when I see it in a Rembrandt, or Hals,

but a great Chinese painting appeals to a more subtle and rare and

finer perception in me.

Now

the sitter comes into my studio and there begins the adventure I

have looked forward to with so much excitement and such great hopes.

Here is my chance to compete with the great men whose pictures I

have pored over-who are my heroes. That challenge, as well as the

challenge to create life is one of the chief incentives. If the

sitter is a friend, I have preconceived ideas about him, a multitude

of them. If he is a well known person I have preconceived ideas

about him. If he is a total stranger, the first impression his looks

and his presence makes upon me probably will dominate my portrait.

My habit of making myself sensitive to the present moment comes

to the fore. In any case I treat the sitter as a new experience.

I move him around the studio looking at him in different lights,

looking for the salient characteristic shapes. The vividness of

the likeness depends on the forcefulness with which the salient

characteristics of form and color are described in the portrait.

I watch for what may be a characteristic pose all the time looking

for the elements in that pose, perhaps a crossed leg repeating the

diagonal line of a shoulder against a light background, perhaps

the tilt of a head echoing in the reverse direction the gesture

of a hand, or the slant of the body. As I said, all this is half

impersonal, half having much to do with the man's character.

Tom

Girdler, the steel magnate, came to be painted. What I had read

about him gave me the idea that he was a rough, overbearing person,

and so I was delighted when he sat down, crossed his knee and grabbed

it with his hand like a claw, with all four fingers extended. By

putting a table behind him I could get his other hand to repeat

the action on the edge of it, and so I had a repeat of abstract

design and what I thought was a gesture descriptive of the man.

At his first rest, he walked about the studio and said: "This

is the most disorderly room I ever saw." When we said goodbye

at the end of the last sitting, be said: "I'll never get myself

into this sort of thing again." Perhaps if I had known him

longer I should have done him differently; but the portrait as a

portrait would have been no more vivid.

The

quality of a caricature to an extremely subtle degree, which may

be more pleasantly called emphasis, is very important in portrait

painting. I remember President Eliot asking me why I did not measure

his height exactly. "Because", said I, "I want people

to say 'What a tall man!'"

If

I am to tell what goes on in this artist's mind I must give examples.

There was the case of Calvin Coolidge. When he stood before me I

saw a commonplace Yankee face, with features not salient, with nothing

for my mind to grasp. Making myself impersonally sensitive to my

first impression gave me nothing like a President of the United

States. You can judge whether I was an honest man or not. Tarbell

had painted him the way he appeared in a mirror. I said to myself

"I am painting a former President". By arranging him in

strong light and shade I found he had more nose than had at first

appeared. I found he had evident cheekbones, and so I emphasized

these characteristics. His mouth looked narrow and set. I didn't

slight that characteristic, and by emphasizing the slight oblique

set of his eyes (presumably inherited from an aboriginal American

ancestor) I made a man who looked like Calvin but also like what

I thought was a man of some force.

Having

decided on a possible pose, next I make pencil sketches to enforce

it on my mind. Then I make an oil sketch of the head and another

of the pose. I make this sketch of the head as forceful and simple

as I can, with no detail, but the large relations of light and shade

and the mass of the head. This may look to some like a caricature.

But often it has (though not so much like in detail as the finished

portrait) so much vitality that it is liked by the sitter in after

years better than the finished one. That is because vitality is

the most important attribute, after design, in a portrait.

People

react very differently to these sketches. Some of you remember Professor

Joseph Beale of the Law School, not a handsome man, far from

it. He was intensely interested in all my processes, including the

caricature sketch of his head. That helped me to make one of my

best portraits. It went easily. Another gentleman in a high position,

a scholar and a brilliant man, on seeing the study of his head,

said: "I was willing to sit to you, supposing you were going

to make a dignified portrait, but if you do a thing like this, I

will not!" I finally made him see my point of view, but all

that didn't help the portrait!

There

are many influences which make me paint portraits. There is a certain

amount of exhibitionism of wishing admiration from one's fellow

men. I imagine I would rather paint purely to please myself. I said

to Professor Kilpatrick, teacher of pedagogy, as I started his portrait:

"Now, for the hundredth time I am going to try to paint to

please only myself." "You can't do that," said he,

"Why not?" "Because you are using a means of communication."

I am sorry to say he is right; but most of the time, at my best,

I am only interested in making the best work I can in order to fulfill

the challenge. For there is a great challenge. To create a sensation

of life. To do a first rate job, to vie with the great and splendid

painters of the past, to try to make beauty, and to try to find

new ways of doing it. You remember Justice Holmes used to say that

one should do a job as well as one could, and then not advertise

it.

So

far, I have spoken only of painting men. How about portraits of

women? A newspaper critic in New York, writing of an exhibition

of my portraits, once said I was good at business men and academic

sitters, but when it came to women, "No; he makes them look

good, and not dangerous". As I think back, I can't remember

any woman portrait at that particular show except that of old Miss

Lizzie Putnam, who was certainly one of the saints of the earth.

But if emphasis of peculiarities is necessary to making a likeness,

how is a painter to emphasize the feminine beauty that Nature has

already put in the woman? It is there already in its perfection.

Think of all the portraits of beautiful women that artists have

tried to make. How much finer and more moving are the plain women

by Rembrandt. And look at the magazine cover girls. Sir Thomas Lawrence

came pretty close to them. And can you imagine Lord Nelson throwing

away his reputation for a woman who was only Romney's version of

Emma Hamilton? Emma was a good deal more than that, I wager. So

often what is called beauty is only nature's way of continuing the

human race. The beauty the artist sees in a woman's face may be

far more dependent on what her spiritual nature has done to that

face.

Awhile

back I was telling about experiences with sitters. Perhaps I can

entertain you with more. Painting the portrait of Mr. Justice Holmes

was one of the exciting experiences. He was very old but very vital

with a face of great architectural beauty animated by a gallant

spirit. He would change suddenly from mischievous ribaldry to an

earnest, statement far up in the region of ideals. He asked me to

stay to lunch one day and after he had been rested by having his

secretary read to him Confessions of a Chorus Girl, the conversation

at table between him, Felix Frankfurter and Professor Cohen was

so far above my head I couldn't possibly reach it. Another time

not so long after he had handed down the dissenting opinion on the

Rosika Schwemmer case, quoting the Sermon on the Mount, when he

heard his secretary and me congratulating the world on what the

League of Nations had just done toward peace, he said, "You

young fellers don't know what you are talking about. Once in a cavalry

charge a Reb slashed at me. I pointed my pistol against his chest.

The damned thing didn't go off. I wish to Hell I'd killed that man".

Did I put an extra twirl in his cavalryman's moustache after that?

One

of the very pleasantest commissions was naturally enough the portrait

of Bliss Perry, and the more difficulties I got into on the shadow

side of his face the better I liked it for he had to keep coming

until it was right, and that meant hours of pleasant talk.

I wish

every one could have as much training in drawing and painting and

learning to see as he has in reading and writing and arithmetic;

for all around us all the time are millions of combinations of form

and color and subtle relations of one to another, all of which to

the understanding mind make beauty. It is all there for the taking.

The portrait painter is especially blest, for his interest in people

brings him close to his fellow man. It may bring him temptations

to feel a false superiority. "Here is this great man before

me but I am his master here with my brush and palette to depict

him as I want to." That is comforting to the inferiority complex.

The more the portrait painter is humble before the wonders around

him, the nearer he can come to seeing the beauty that the fine nature

can give to what is casually known as a plain face he can finally

perhaps come into real communion with the spirit of his fellow man.

|